Have you ever heard the term, High Net Worth Individuals (HNWI)?

Sounding a lot less intrusive than “is someone rich enough”, it asks the same question, with a higher chance of getting a straight answer: are you rich enough… to afford certain things?

In the States, the land of capitalism, the definitions of HNWI have largely converged into $1M to $5M as entry-level rich.

In Australia, there is less consensus about what the magic number is, ranging from just over $1M liquid assets, all the way to $50 million by the Australian Tax Office.

It would’ve been easy to pick any one of the existing HNWI definitions to stratify wealth. It is an established part of the financial world’s lingo, and we are talking about money and wealth, so why not use this existing definition that’s part of that world’s system?

It’s useless, to begin with. At least for now.

Finance’s typical stratification of wealth is commonly used by investment-seekers to determine their ideal investor pool. 0.0025% of one’s total wealth, you’d agree, sounds like a relatively small sum, but 0.0025% of someone’s $1,000,000,000 has a vastly different magnitude than 0.0025% of another’s $1,000. If one gets the same 0.15% cut for managing either amounts for almost-equal hassle, who wouldn’t choose the first one?

The usual definition of richness, commercially, is more about quickly finding out how likely you are to hand over $25,000 to them than it is about what $25,000 is in the context of your life.

A $25,000 is a $25,000 is a $25,000.

But is it a whole life, a year’s, a month’s, an hour’s, a fraction of a second's worth of one’s time and energy?

So as financial firms are wont to do, we, who want to excel at money, can apply that same logic: we, too, can define our own stratifications of net worths, in a way that serves us.

I’m not a financial advisor, and this is not a financial advice.

The good news for the both of us is that one gets certified as rich after acquiring $X million, instead of as a prerequisite to.

In a statistically satisfying event, my small pool of early subscribers represented a great sample of the greater populace: that most people are concerned with going from $0 to $100,000.

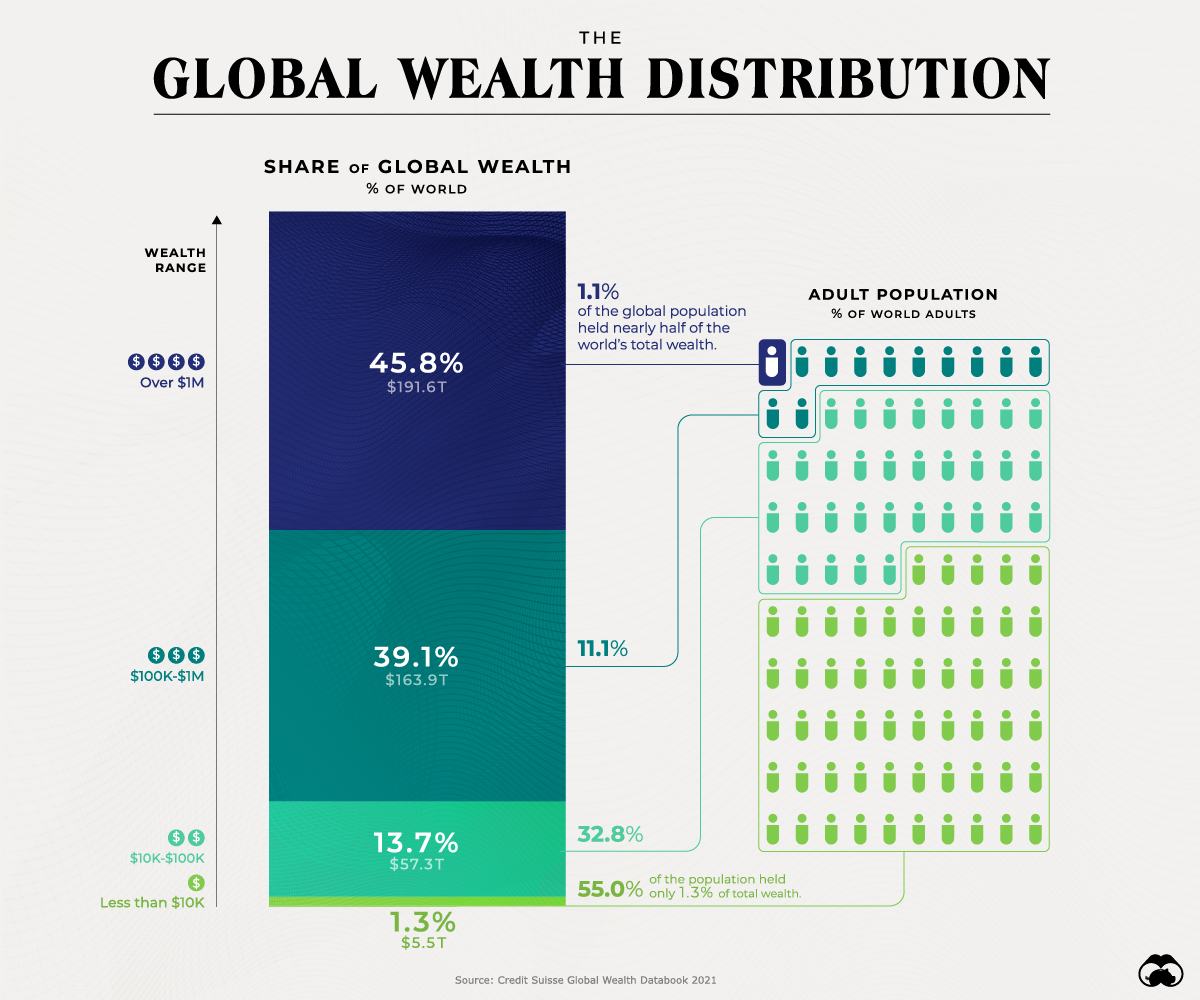

Life in the $0 — $100,000 bracket is perhaps the most diverse, if only for the fact that it’s where most people are. About 87.8% of the world's population in 2021, in fact:

As one might have intuited, accumulating $100,000 in a “third” world country is a lot harder than it does in Australia. Think of it this way: the equivalent of accumulating $100,000 in a third world country would’ve been closer to how one would go about amassing $10,000,000+ in Australia.

When your job only pays $300/month, even if you can save 50% of your income, you still can only save $150/month. The same effort, applied in a context that pays $3,000/month, will net you $1,500/month.

Two identical real returns, different nominals. One guess as to which one will get you to $100,000 faster.

Money is the measure. Even though it doesn’t capture the full value of things, it is easy to do. Do I have $100,000 or not? Nowhere does it say what a $100,000 life looks like. Quantity is comprehensible, but quality is ever-elusive.

When I write about reaching $100,000, it is in the context of per individual, working in a good enough job, usually for someone else, in a good enough place that allows you to save, usually in a first world country.

Just enough, that one can survive to begin with.

Then we can talk about dreaming of a bigger life.

$0 — $10,000 is the survival band.

It’s about making sure that one has enough to live on each month.

Then one pushes her limits, raising income and lowering spend, so that there is something to retain. This margin is how one can start building wealth.

The big question in this band is: do I have enough to survive?

When it costs an individual roughly $3,000—5,000/month to live, allowing for increases in unexpected expenses (but never unexpected income), $0 — $10,000 is roughly 0-3 months, or one bad luck away from not affording to live.

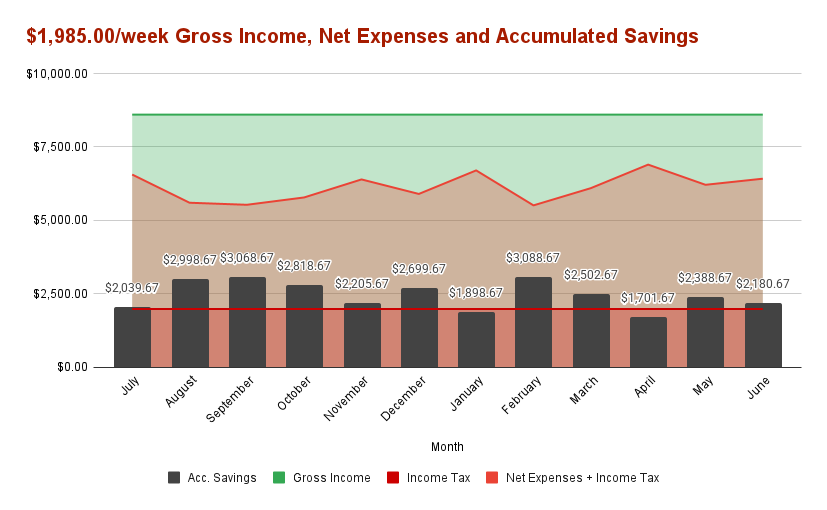

Under the ideal circumstances, an “average NSW salary” grossing $1,985.00/week can afford a “Sydney average” living expenses, which looks something like this:

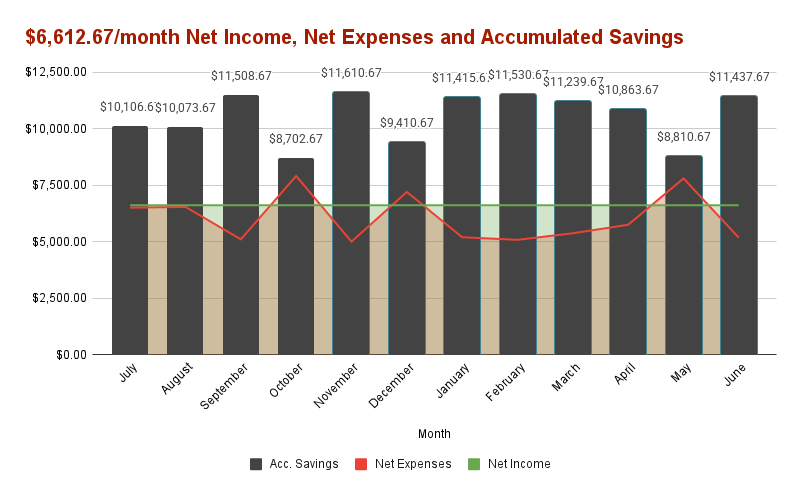

$1,985.00 weekly gross pay is $1,526.00/week net, or $6,612.67/month net take-home pay.

When the bare minimum needed for lodging costs $450/week, $60/week on utilities, $100/week on transport, and $300/week on food, $616 saved weekly by never going out sounds achievable.

The idea of living an ascetic’s life isn’t for everyone, but it is doable, especially if you know that you’re doing this short term for the future.

But what about the long term?

The Expense Gravity

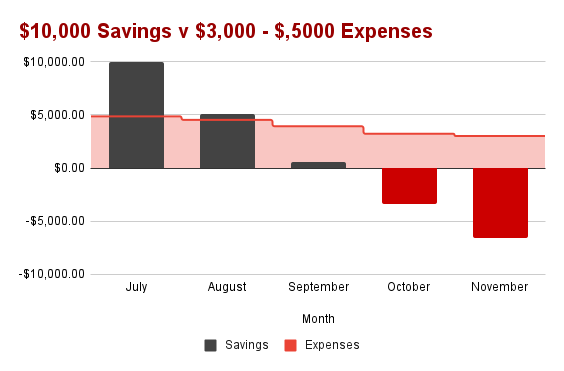

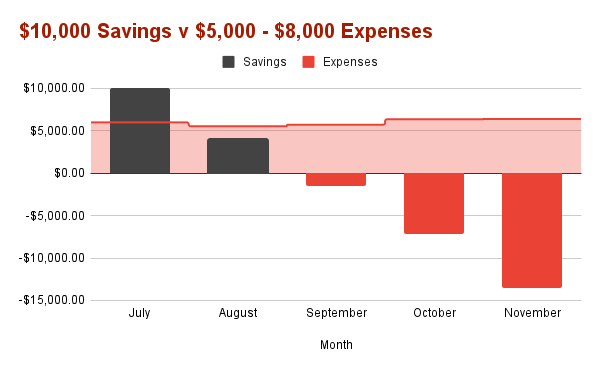

Let’s say that this hypothetical person, riding the high of the new year’s resolution, had managed to save up $10,000 by July.

They thought, “I’ve got this”, and would play it by ear. And they did — sort of.

Their savings never dipped to $0, but they didn't exactly know where their money went each month, either.

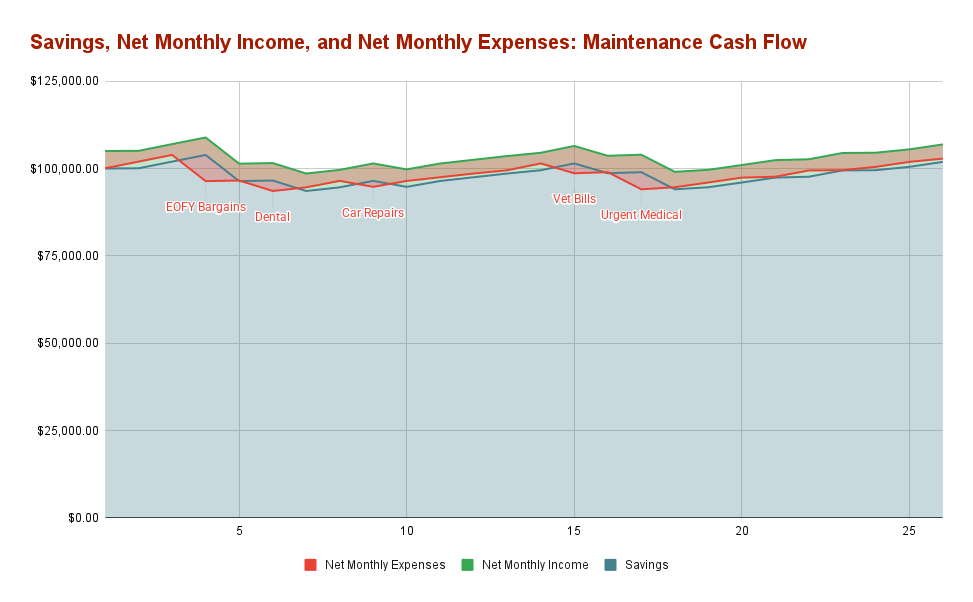

If the end result is such that one maintains an equilibrium of $10,000 in the bank, the only way it’ll remain so is if some months are surpluses, and other times deficits, averaging out to match the net income component in order to remain gravitating around the $10,000 net worth:

What does $10,000 afford then?

If one were to lose their income, one has < 2 months to replace it, because what it’s attempting to afford is not the average expenses of the population, but rather this particular individual’s rolling average living costs:

Population average is of little use when it comes to measuring one’s actual runway, when the real key to individual affordability is the rolling average of one’s expense habits.

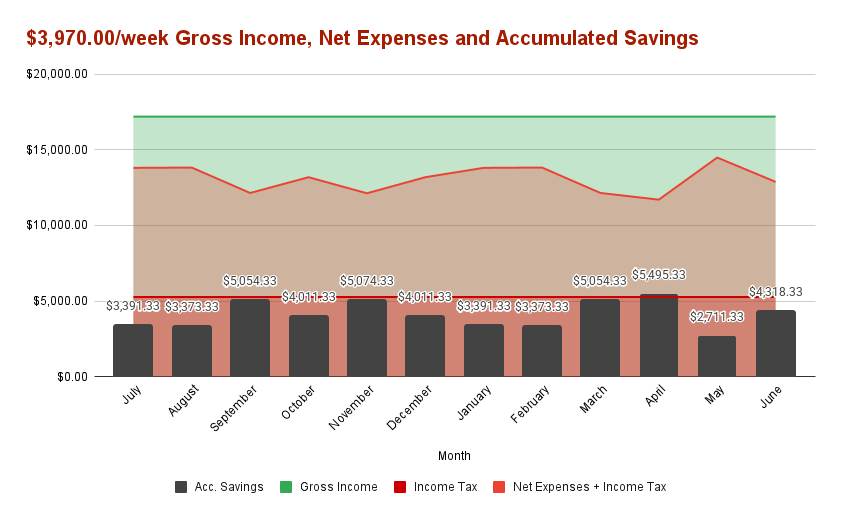

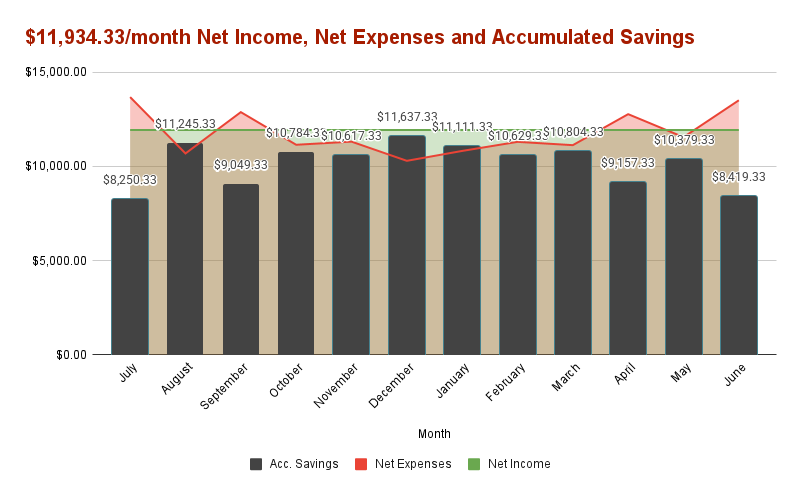

In what looks to be the opposite end of the spectrum, someone else is earning double the “average NSW salary” of $3,970.00/week gross — or $11,934.33/month net — single handedly. Suppose their spend also doubled to suit their pay band, ranging from $6,000 — $10,000 instead:

Person #2 would still save faster, despite having doubled their average expenses and paid more tax. Extraordinary income does cover for extraordinary expenses in this case.

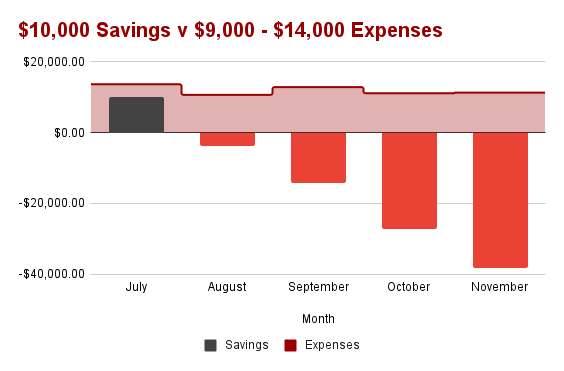

However, if their lifestyle only resulted in $10,000’s worth of savings, their spend is more likely to be around the range of $9,000 — $14,000:

It gets worse. What lasts the “average” person 0 — 3 months can only last them ~1 month under their averaged individual spend:

Leverage is a knife that cuts both ways.

There is a certain flavour; a mix between schadenfreude and disbelief when people see a “high earner” on struggle street. One is tempted to think that these examples are made-up, cautionary tales of the scarlet robe kind, but they do exist. They’re just not very visible; a self-preservation instinct, if you will, seeing as the stakes are much higher.

How they got there, you’d have to ask the specific person yourself; but the most tragic answer has to be that one lives too much in the now because they’ve given up on the future.

In an ideal world, no one has to cut corners in order to afford the bare minimum.

In an ideal world, everyone has the financial literacy to understand the rules of the game.

But that’s not real life… in a lot of places.

A dirty place is better than the streets. A low-paying job is better than no job. The wrong income is better than no income. The best time to start was 10 years ago.

In lieu of all of the above, the second best place is here, and the second best time is now.

Defying Gravity

Both the “average individual earner” and “average household earner” share one thing in common: they are subjects of their expenses’ gravity.

Going from $0 — $10,000 is one of the most tedious things on earth, because there’s so much work involved for little to no results, in a world where only results are valued.

If you already live on the bare minimum, you don’t need yet another person to come and tell you to earn more. You “just” need to do the work of opening doors: getting the right visas, licences, certificates, referrals, to get into the rooms that you don’t feel, or was told that you don’t belong in, in order to get paid more.

If you spend on the high side, you also don’t need yet another person telling you to cut your spending. The work is to sit down and shut the doors... to spending, and other proxies of it. If you earn high and spend high, that’s a lot of other people’s dreams and wishes living in your head, charging you rent on your own space. Remember this adage well: your margin is someone else’s opportunity.

To put it bluntly: defying gravity asks you to first get over yourself.

Living in the $0 — $10,000 band is painful. Going against gravity is also painful. When either ways of being is difficult, why not as well pick the one with the most upsides?

It will suck; as all the work of showing up for yourself do.

It’ll be slow, and it always takes longer than expected.

You will compare yourself, because feelings don’t understand concepts like different starting points, knowledge inheritance, and applied contexts. The homo economicus is a mythical ideal, much like the person who’s perfectly “average” in every aspect.

But the alternative is to live like this for the rest of your life: on a rolling 1-3 months basis, payslip to invoices, and when you couldn’t work anymore, to live on the conditional, “wrong” money.

The first step towards making real changes is to acknowledge how things are in one’s life, as they truly are, without judgement. It does not come from empty complaints about how things should have been, for systemic changes takes years — decades, well into the next generation — which does not help if one needs to eat now.

These should’ves, could’ves, and ought’ves all consume one’s focus: the one thing that’s to be funneled 100% into escaping gravity.

First comes a wage. Any wage to cover the corners that one can’t cut.

Then comes a better wage. When there’s nothing left to cut, one can only add.

Most importantly, when it comes to facing the ghosts of “but how long will this take” or “I can’t afford to fail”, what is there to lose when there’s nothing left, where this current trajectory is heading towards?

Then, and only then, can one start to afford the privilege of having ideals.

Feel the suck, and keep walking.

$10,000 — $100,000 is the foundational band,

so learn to build a strong foundation.

It’s about making sure money in > money out every month. If what goes in equals to what goes out, one can never accumulate. The simple end result, the one final figure that we come to after skipping all of the complex hows and whys of it, is that wealth is what remained.

For many, this is where the greatest transformation happens: becoming someone who can build wealth.

The big question in this band is: can you consistently keep what you earned?

In the game of wealth there is only 1 end component: the amount unspent.

The amount unspent, in a post-barter society, is the closest thing to having real choices. The right kind of money represents real choices, ones that are not subject — for the most part — to the usage terms and conditions.

To accumulate wealth we play the game of finance, in which we seek the —potential— answers to the 2 components that resulted in the unspent amount: net income(s) and net expenses.

To appropriate another finance term, the higher one’s ceiling is and the lower one’s floor goes, the more breathing room one has.

The Income Component

If you have a fulltime job, finding out your ceiling is easy. Monthly salaries under the PAYG system comes in after tax, thus is already a net income.

We’ll talk about pushing your ceilings the salaried way — benchmarking, positioning, and ROI on degrees — in a separate post, as this topic is more opaque than expense benchmarking.

A few bank interests and dividends at this level is spare change. Every cent counts, but is hardly something to fuss about for hours on end.

If you’re working multiple part-time jobs, that too, is fairly easy, because the tax man makes it so you can one-click to generate taxable income reports. If you take cash and haven’t gone bankrupt, you’re already an expert and should skip forward.

The Expense Component

The expense component gets all the attention when it comes to the foundations of financial literacy. Rightly so, because expense varies a lot per person, and with high variance comes inefficiencies, thus is where the highest potential of improvements are to be had.

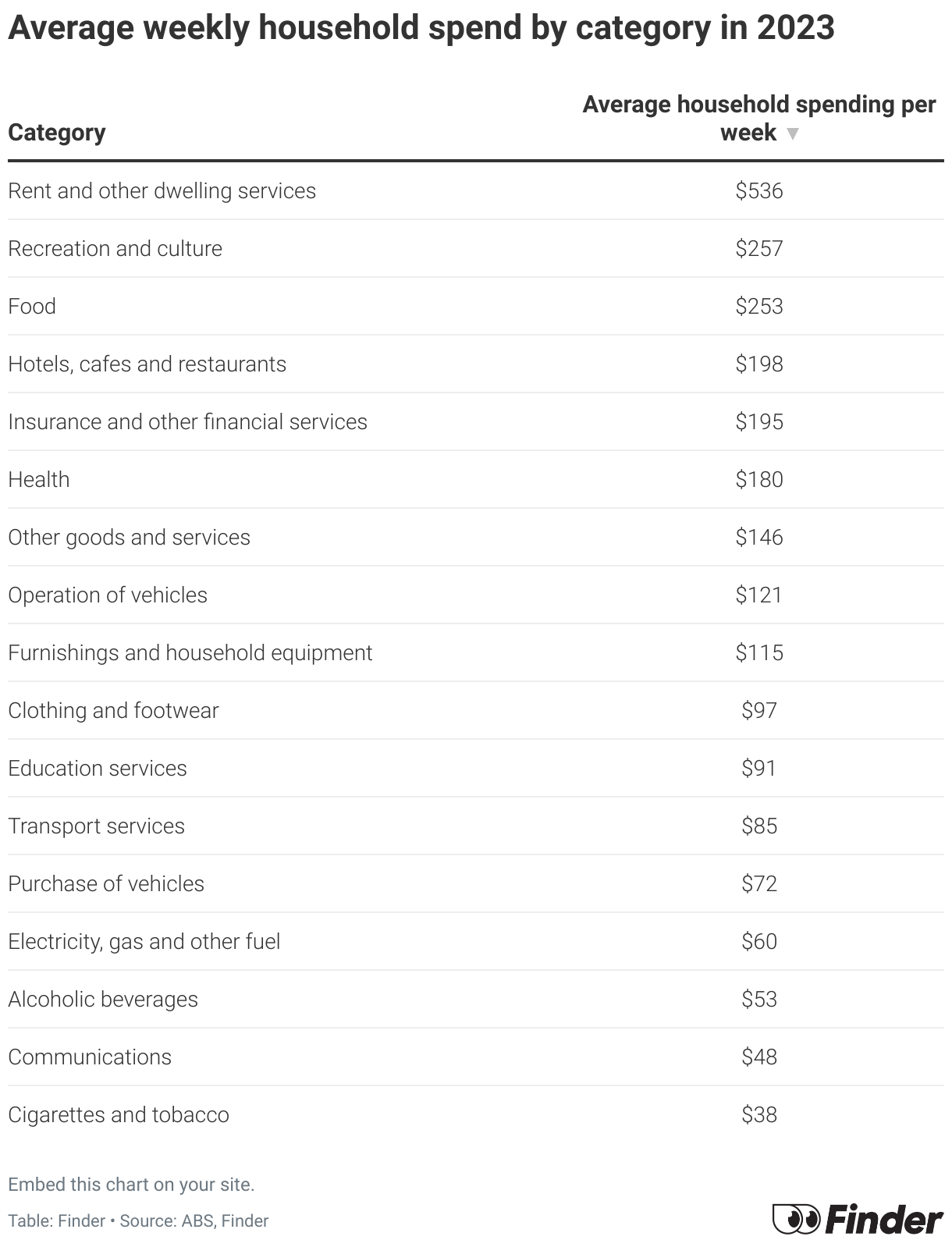

A good floor level to aim is the average of what other people spent based on a publicly available data, from ABS or from other comparison site's reports. They're not perfect, they're likely to be outdated, and they certainly don't all apply to your personal circumstances, but it’s a good start, because population average is proof that that expense level is affordable for most people.

If your circumstances are more complex than this, you have to try harder to find the subset data of people who are most like you, or get a financial planner; it is their job is to keep tabs on those like-benchmarks, as a prerequisite to giving a useful, tailored advice.

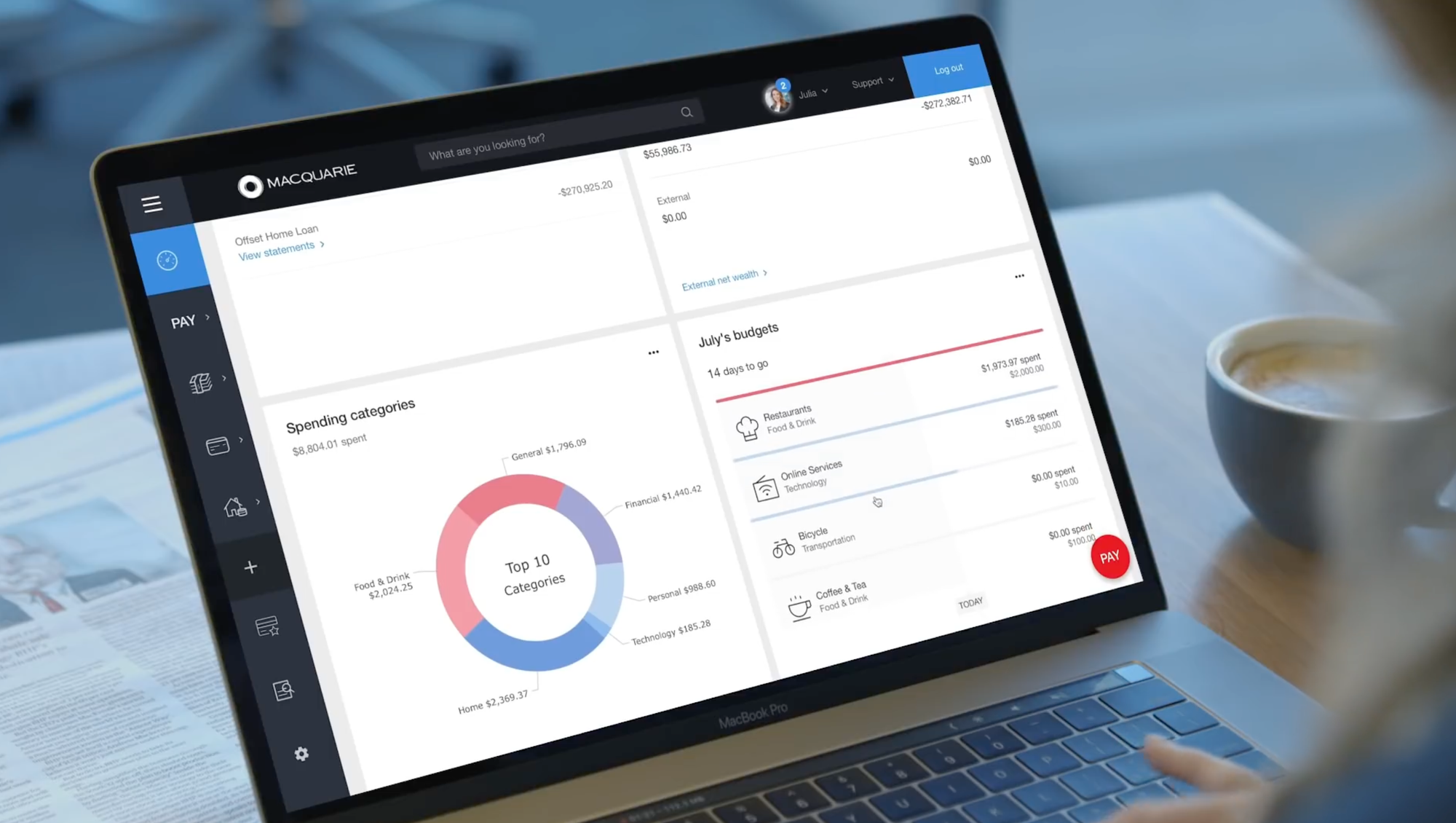

If you can make do with a generic average spend, there is one thing left to do, and that is to make a habit of reading up your expense reports.

The thing about the spending habits is just that: habits.

Live long enough, and one accumulates things just because, regardless of whether or not they still suit us. The proof is in the many new parents who can suddenly find the spare $20,000/year net to raise a child, despite living hand to mouth prior.

That’s what happens when one gets clear about what really matters.

That it still so often requires bringing a new life into this world in order to make it a priority is a testament to how far we’ve yet to go, when it comes to thinking of ourselves as inherently worthy of the effort.

Keep it simple. Generate your expense report. It’s all there. You just have to sit down and read it, and save the judgement for when you can afford to.

And when’s that?

When your bank account’s line goes up every month without having to think about it.

Your receipts form the tapestry of your desire. Keep them, understand them, and get to know yourself.

Sort them from the largest to the smallest, and chip away.

For a lot of people in good-enough jobs, this band is comfortable.

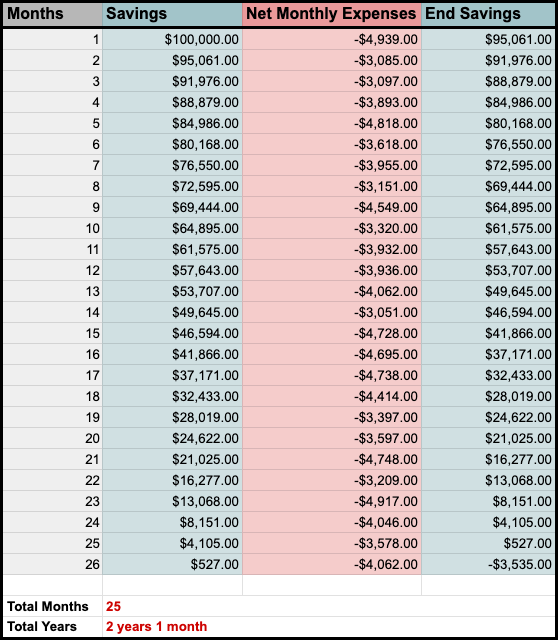

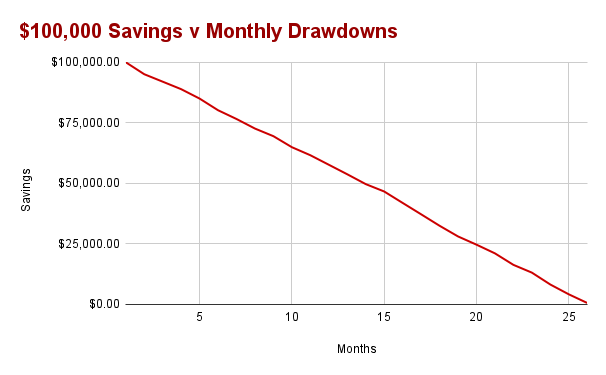

From the average cost of living perspective, having $100,000 in the bank means that one can have ~2 years of runway should one loses their income. For example:

Individual circumstances will vary, as we have seen.

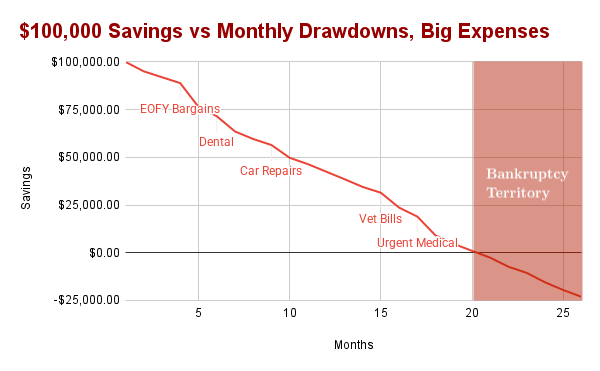

Having $100,000 means that even if there’s no income, one can still pay for those big expenses and live on:

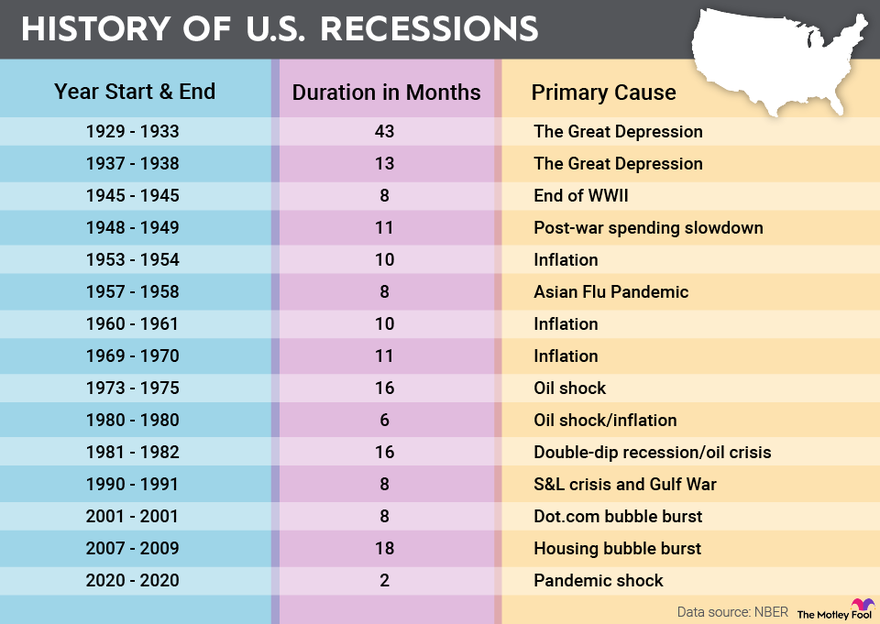

If and when inevitably a recession happens, since most recessions had “only” lasted for < 20 months, it means that a single person on an average individual spend will have a good chance of making it to other side of the recession, when the market recovers and people start hiring again.

Knowing this won’t make the recession feel any shorter as you live through it; however, when all seems dark, knowing there’s light at the end of the tunnel is the single candle that holds one throughout.

Under business as usual, $100,000 buys a lot of things, not the least is the peace of mind that comes with knowing that one has enough to weather most sudden life expenses:

It doesn’t make any difference to wealth accumulation, since the cashflow model here is what goes in ≈ what goes out.

What $100,000 on hand does is essentially to act as a private safety net; the privilege to afford things that one’s ordinary income can’t pay for, that doesn’t require any begging or queueing up.

What this means is that in order to start building wealth, you must have at least one of the following: an average income on extraordinarily low expenses, or an extraordinary income on average expenses, if one is to start building a margin of safety.

An Average Income for an Average Life

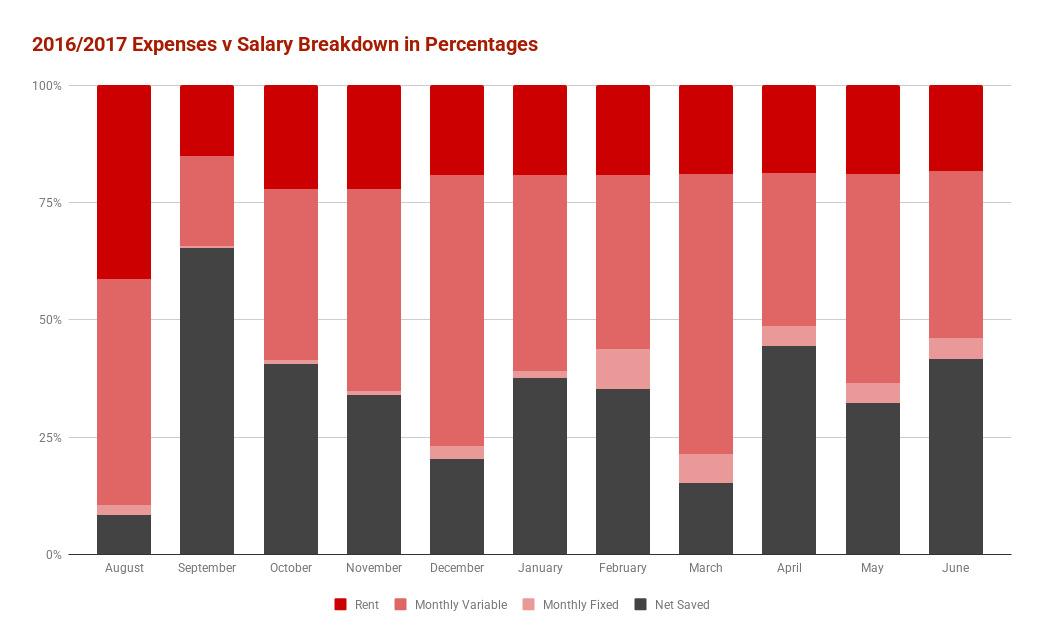

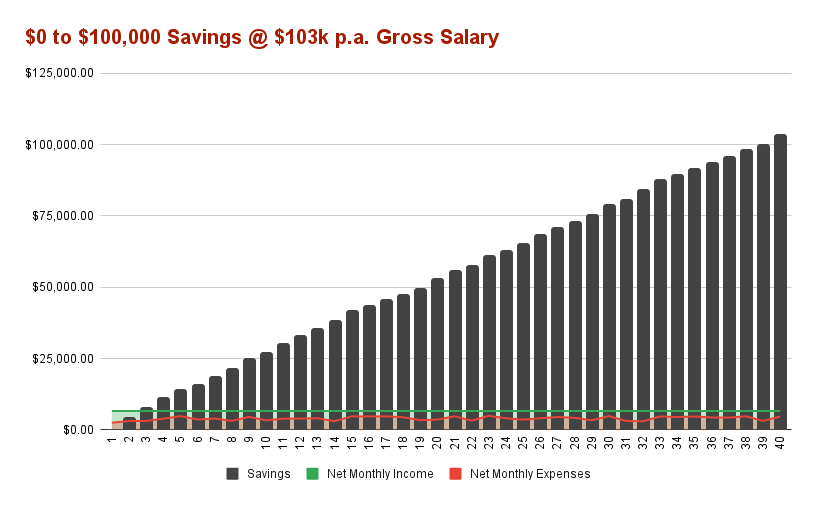

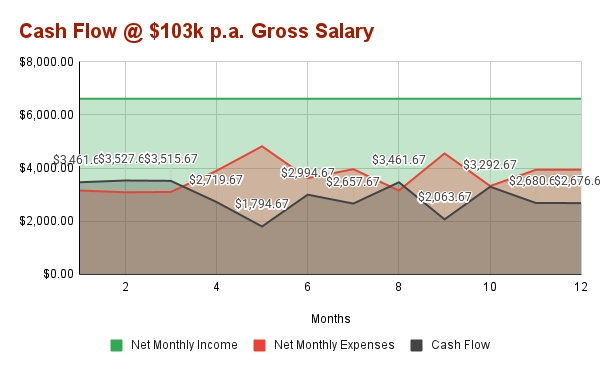

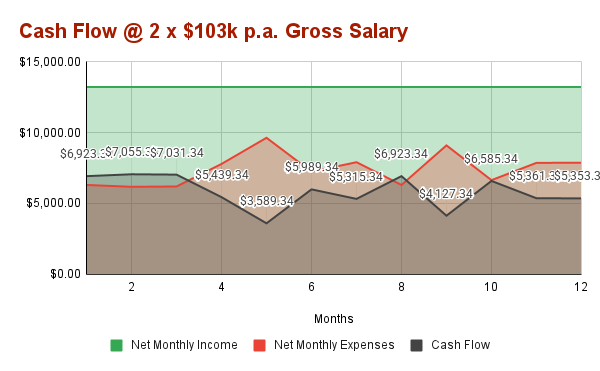

$1,985.00/week Gross Pay, or $103,220.00 p.a. on $3,000 — $5,000/month gets you to $100,000 in 40 months, or 3.33 years — on average:

You save, on average, $1700—$3,500/month:

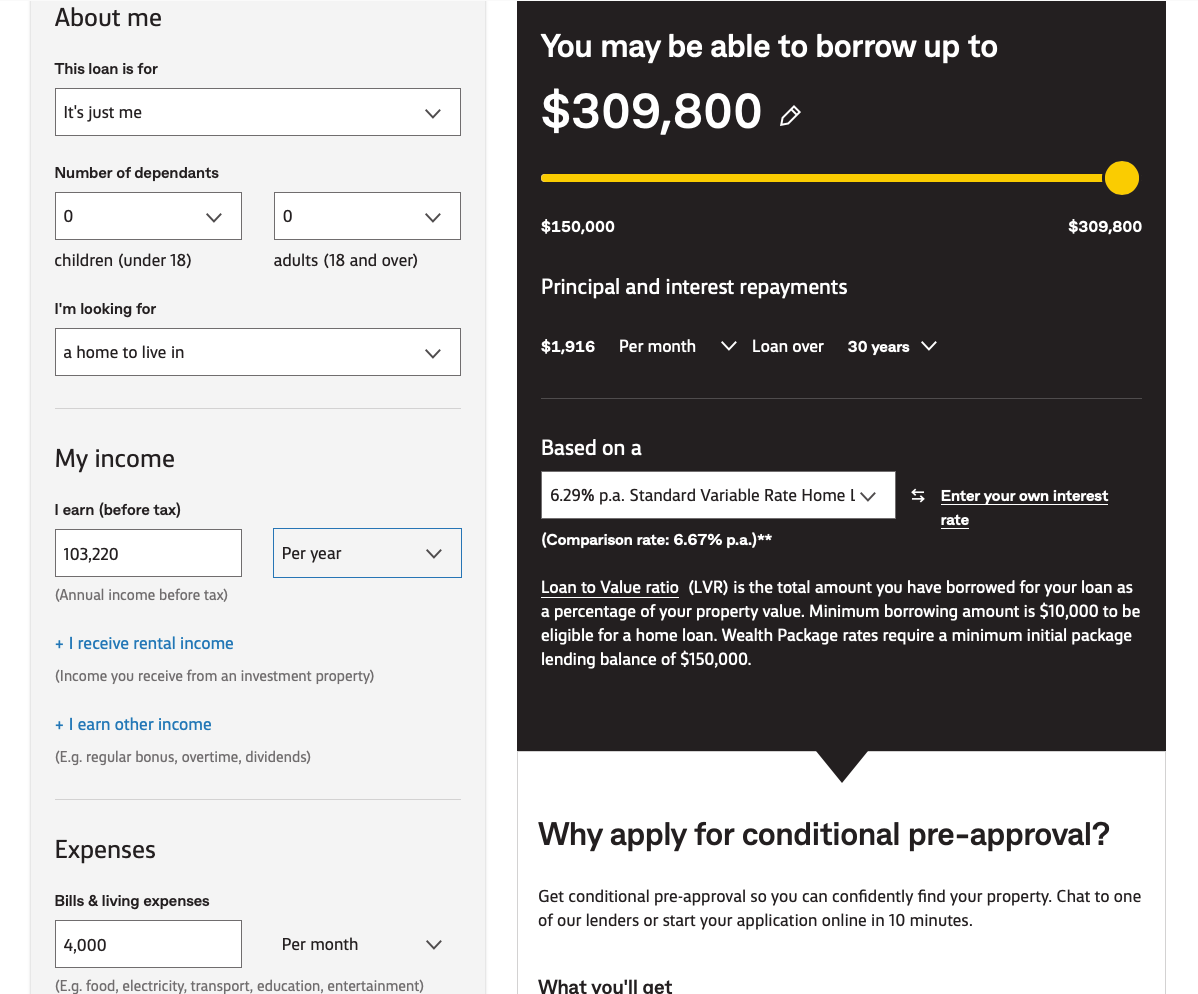

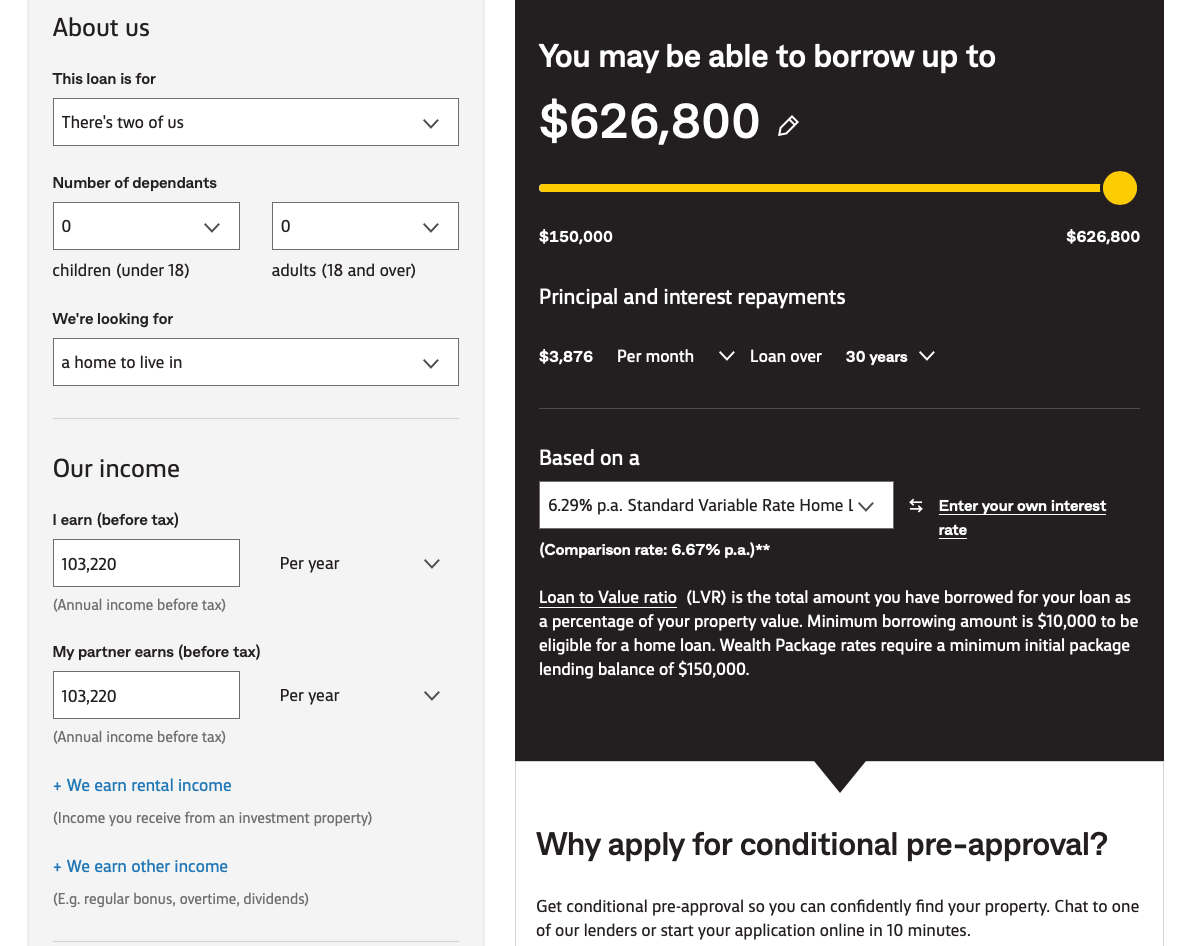

Because you’re on top of your finances, you feel good, maybe you have a good chance at getting a mortgage now to buy a place. CBA came back to you with this figure:

Which buys… nothing, in Sydney, where a shoebox studio starts from $600k. And you’re not that desperate yet to get into a mortgage-based relationship.

…are you?

In a move that has none whatsoever to do with mortgage affordability, you found someone to settle down with.

Your significant other just so happens to have the exact disciplined cash flow management as you, so together you are able to borrow ~$626k to buy your first home (apartment). And you did.

(You might be able to borrow more or less as the CBA calculator doesn't separate the current rent paid from the total expenses field… but that’s beside the point. We’ll talk about that actual underwriting in a post about Affording Your First Home.)

We won’t ask too much where the down payment came from, as it’s not culturally polite to ask about it uninvited. The end result still is that your $100k savings remains intact instead of being tied up into a property.

When the (e-ink) dries, you are now officially the members of Australians’ second unofficial religion: the church homeownership. Congratulations all around.

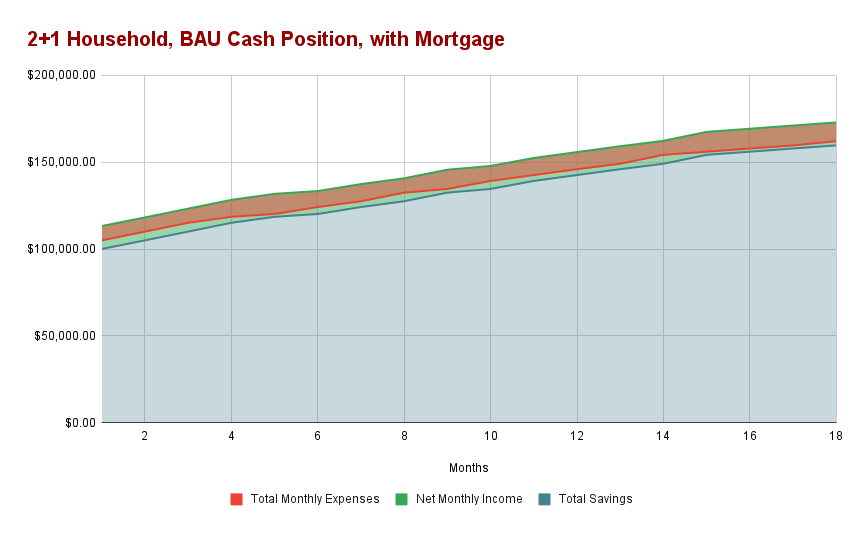

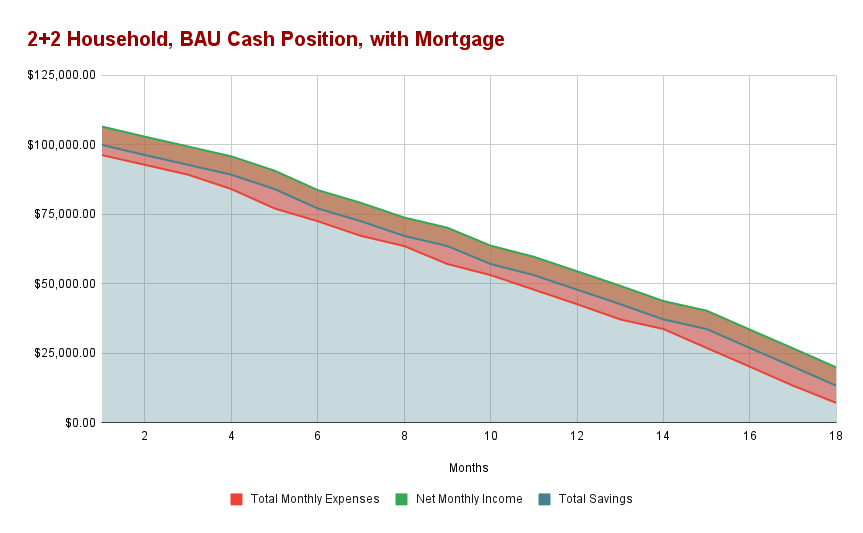

Where you, as a household, had been saving ~$3500 — $7,000 monthly before mortgage (as an oversimplified function of 2x individual cash flows):

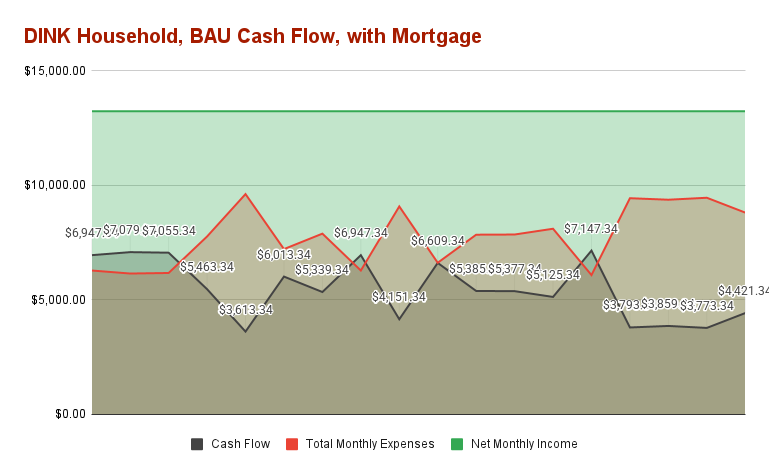

Even after taking out a $627k mortgage, paying $3,876/month on P&I (Principal & Interest) mortgage repayment, your good money management keeps you on a very healthy savings rate, especially that you’re no longer paying 2 x $450/week on rent, adding a whopping $3,900 net after tax back to your cash flow:

Essentially, what used to go into rent now goes into repaying your new property, building wealth. Rent money is dead money, right?

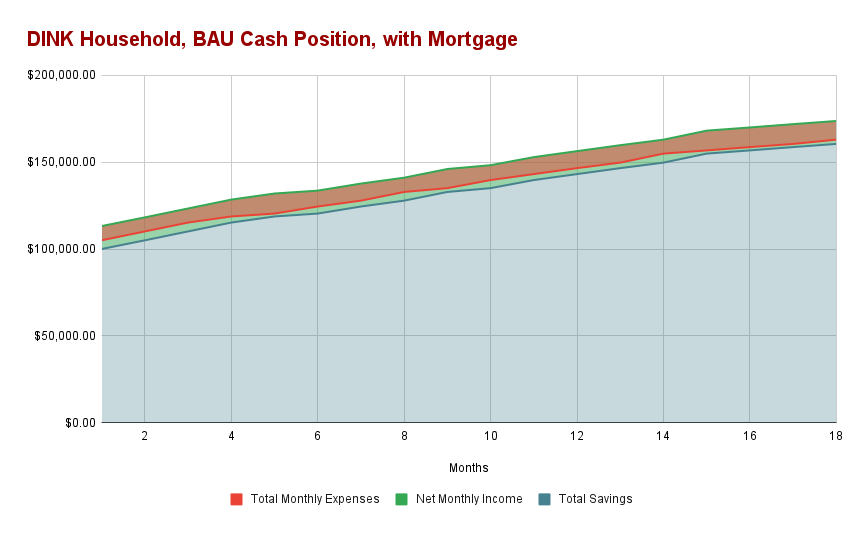

Your savings kept going up, accordingly. Plus, you now hold another asset besides your savings: a property to call your own. It lives on a separate balance sheet that’s not tracked here, as this pertains your cash position only.

You feel good. And you should be. This is what good personal money management looks like.

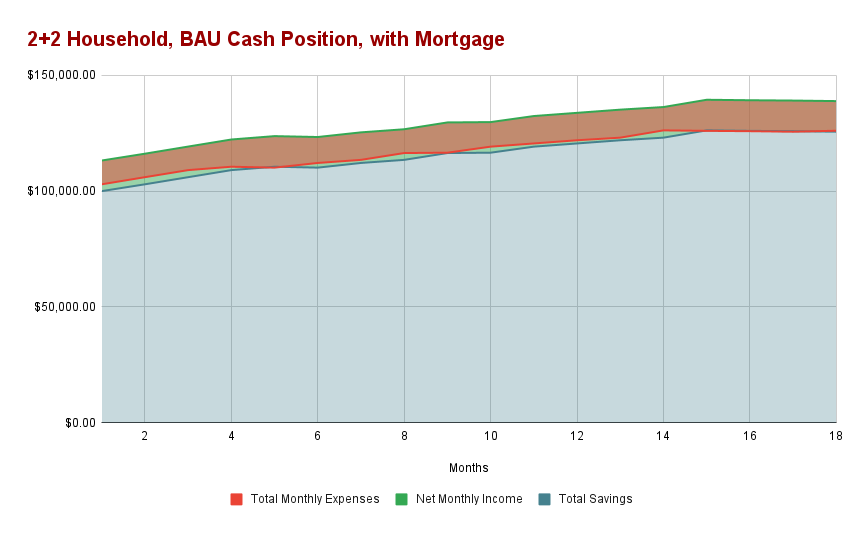

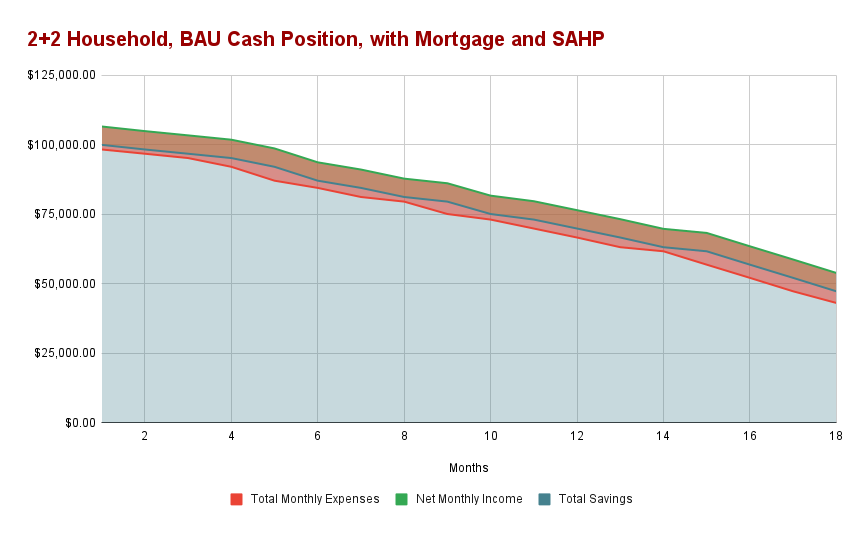

Because there is still some excess cash, there’s room for one more:

And another… it’ll be tight for awhile, but it’s not forever:

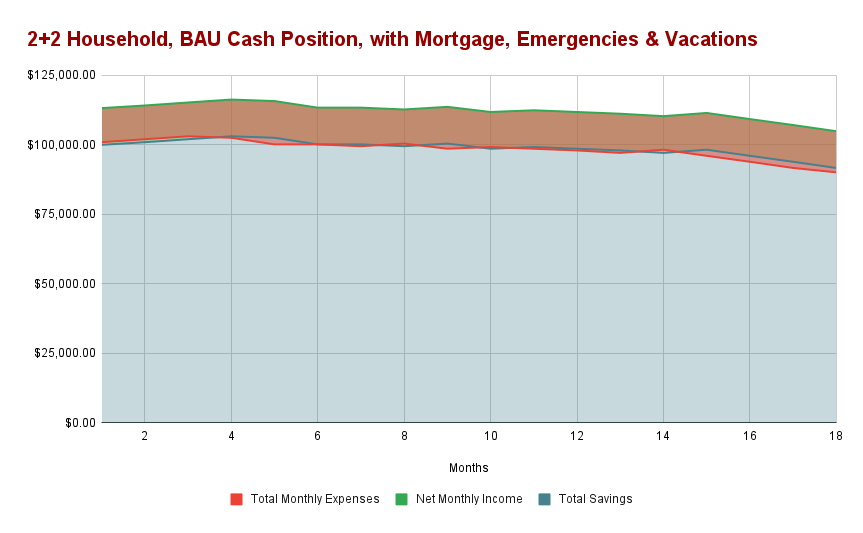

And of course, to account for life’s surprises and family holidays…

It’ll be tight for awhile, but it’s not forever.

Afterall, we still have that $100k of savings to dip into.

In this way we are lulled into a false sense of security, rising our floor with every growing needs as we roll into our next season in life, pushing our ceilings for $10,000-50,000 every 3-5 years — if that.

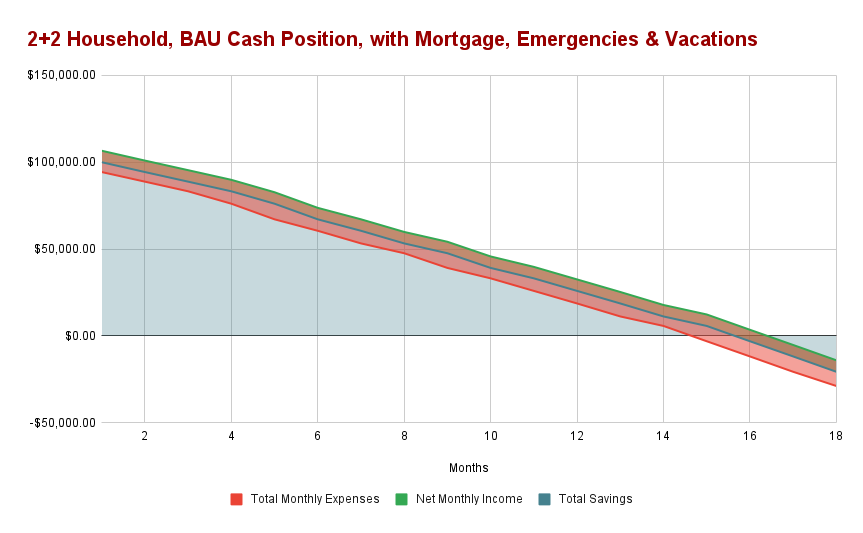

What happens when all of the above happens?

Recessions are rare events; by nature, they’re neither urgent nor important, until they happen. So much so that every generation, collectively, gets recession amnesia. When life as one remembers it had always been good, why prepare for something that has never happened?

When it gets tight, such as when all of the above happens at the same time, one can look for a better-paying job, hoping that the market is benevolent enough that there is such a thing as a better-paying job with not enough qualified applicants.

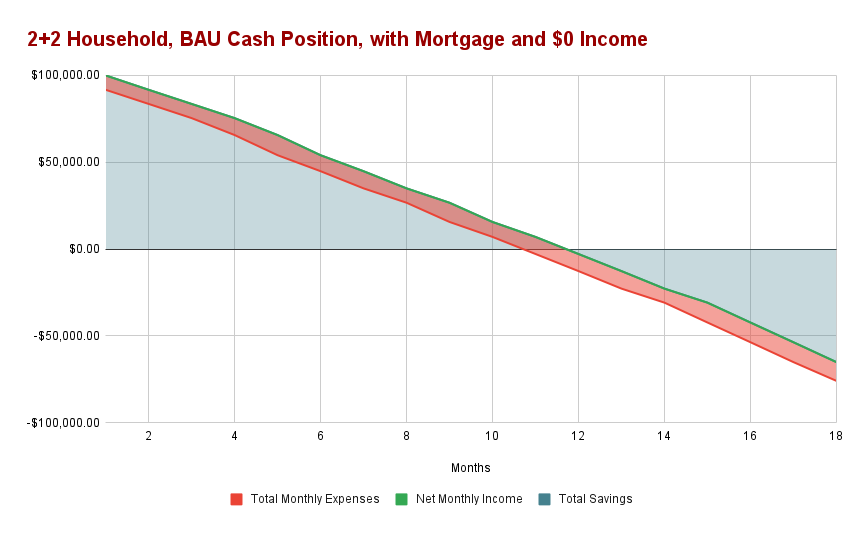

Your sector was hit hard by the recession:

Sensibly, vacations and other discretionaries get cut off, affording you more time.

You couldn’t get another job that nets above the subsidy gap to cover for daycare, so you both decided to that you’d stay at home and become the fulltime primary carer to save costs.

It bought you even more time, on top of the non-monetary benefit of spending more time with your kids:

You might think of downsizing to a smaller accomodation, but there’s 4 of you now. You were already in a 2-bedroom apartment on the outskirts of town, thinking of either upsizing or moving closer to the city centre, before this all happened.

Then the very thing you've been dreading about happened: your partner lost their job, too.

Hopefully, this recession is one of those non-inflationary, 6-8 months recessions, and no one gets afflicted by what Medicare doesn't pay for.

This type of life is good enough when the going is good. The market works most of the time, except that when it rains, it pours.

When there’s rising living costs is when one typically needs a better paying job to offset the rising floor, but the market that’s made up of other people are also cutting costs, including the cost of paying other people’s salaries.

The housing market, too, has a bad habit of shrinking precisely at the moment when one needs to sell.

That’s what this band is all about: living market to market on a 9-5, Sisyphean and small, held up on a prayer for the next good market condition.

"We are what we repeatedly do.

Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit."

— allegedly, Aristotle

Why was the post titled “A Tale of Three Brackets”, when there’s only 2 brackets mentioned?

$0 to $10,000 and $10,000 to $100,000 weren’t even meant to be separate when I first started writing this out.

I initially — and still do — consider $0 to $100,000 to be a single bracket, so there's yet another 2/3 of the point to go through. This is because for people on liveable incomes, good savings habit alone will get them to $100,000 automatically.

What this arbitrary delineation of wealth brackets is based on is about making sure that one can accumulate wealth consistently.

First on your own balance sheet, then another.

And another.

See how far you can go.

I do not wish for us to stop at personal budgeting. Nor do I think that the most we can do is passively invest and hope for the best. That part of wealth strategy has been covered over and over again, in the many blogs that others have written. For that reason, my future posts would be focusing more on exploring the possible pathways towards $10M.

And yet –

The basics drive everything.

Getting the basics right, giving it the proper respect is essential, as it sets the tone to everything that we would do towards $10,000,000 and beyond.

It’s fractals all the way up.

I wish for our conversations to move beyond budgeting, but we can’t talk about capital gains unless we get the cash flow right.

A hungry person can’t be asked to stockpile grains to trade it for buildings and machines, let alone to make bets on the future, instead of begging for scraps in the now.

I hope I had given it the proper respect it deserves, without rehashing too much the same old message.

Money now keeps you going in the game. This is positive cash flow.

Money later gets you out of the game. This is capital, and the many expressions of it: businesses, shares, property, and other assets that are collectively valued by us, for we are the market.

Whatever is practiced on 1 personal balance sheet, will be carried over to $10,000,000 and beyond, because for the rest of us who’s not an elite athlete earning $10,000,000+ annually, the way towards $10,000,000 is through excellence on multiple balance sheets.

All those perks and issues one encounters while managing one’s personal finances? Will be carried over, and magnified.

What can be cut; what should not be cut?

This is the shape of your integrity.

To face the music now is preferable, than when it’s the whole ensemble.

I've made my choice all those years ago.

Your turn.